EXCLUSIVE: No big surprise that today Marvel and Disney asked the Supreme Court to deny a petition from the heirs of Captain America, The Avengers and X-Men co-creator Jack Kirby. “This case presents a factbound application of a test uniformly adopted by the lower courts under a statute that does not apply to works created after 1978,” said a response filed today (read it here). “It implicates no circuit split, no judicial taking, no due process violation, and no grave matter of separation of powers. It does not remotely merit this Court’s review,” added the media giant’s main attorney in the matter, R. Bruce Rich. ... “In likely recognition of the fact that the statutory question does not satisfy the requirements for this Court’s review, petitioners turn to a series of bizarre constitutional arguments raised for the first time in this Court,” says Marvel. “Those arguments only underscore that none of the questions presented merits this Court’s plenary consideration.”The Kirbys are in a tough position here but I have to wonder if Marvel may yet regret pushing that "continuous supervision" line. Here's why [from the very good write-up by Michael Dean in the Comics Journal]:

... Lisa Kirby, Neal Kirby, Susan Kirby and Barbara Kirby petitioned the SCOTUS this spring to hear their much-denied case. The heirs contended they had the right in 2009 to issue 45 termination notices to Marvel and others including Fox, Sony, Universal and Paramount Pictures on the artist’s characters under the provisions of the 1976 Copyright Act. While Kirby was publicly identified with much of the comic company’s prolific period along with Stan Lee, Marvel has won before in the courts under the understanding that the 262 works in question in this case the comic legend helped create between 1958 and 1963 — including many of the brightest stars in the Marvel Universe — were done under a work-for-hire deal and hence he nor his heirs have any rights of termination. With that in mind, Marvel initially waived any response to the SCOTUS petition. However, then the High Court itself requested they respond as the justices took the matter into conference. That initial scheduled May 15 conference was postponed as the Court awaited Marvel’s response.

“Petitioners alleged that their father, Jack Kirby — a freelancer who contributed to Marvel works in the form of commissioned drawings and under Marvel’s continuous supervision — held copyright interests in those works,” said Marvel today summing up the other side’s case. Now the response from Marvel is in, the Justices could take the matter under consideration. If they agree to hear the petition, it will be scheduled most likely for their next term which begins in October.

...

The case is starting to attract some superfriends now that it is in the big court leagues. Last month, SAG-AFTRA, the WGA and the DGA submitted an amicus brief to the Supreme Court in favor of having the petition granted. “The Second Circuit’s holding in this case reaffirms a test that created an onerous, nearly insurmountable presumption that copyright ownership vests in a commissioning party as a work made for hire, rather than in the work’s creator,” said the 32-page filing of June 13 (read it here). “In doing so, it jeopardizes the statutory termination rights that many Guild members may possess in works they created. Accordingly, the Guilds and their members have a significant interest in the outcome of this critically important case.”

The case did not go to trial, but during the discovery phase, testimonies on both sides were collected in deposition. Testifying on behalf of Kirby were Silver Age Marvel artists Jim Steranko, Joe Sinnott and Dick Ayers and comics experts Mark Evanier and John Morrow. Lined up on Marvel/Disney’s side were Roy Thomas, John Romita Sr. and Larry Lieber, but the key testimony that seemed to carry the greatest weight with Judge McMahon came from Kirby’s erstwhile creative partner Stan Lee. The 87-year-old Lee gave a two-day deposition in support of Marvel. Based on the depositions, McMahon formed the following picture of Lee and Kirby’s working relationship: Lee gave Kirby a premise in outline and then “created the plot and dialogue for the characters after the pencil drawing was complete, [and] often times ignored any ‘margin notes’ submitted by the artist with suggestions as to the plot or dialogue in the story.”My knowledge of the law here is limited to about three minutes on Wikipedia but if the judge improperly excluded testimony, that would seem to fall under the heading of reversible error. Evanier and Morrow are arguably the two most recognized authorities on this subject and their version of the Marvel method where certain artists (particularly Kirby and Steve Ditko) would often add major story elements seems to be the expert consensus. Note Dean's line "may have difficulty imagining" (and for the record, The Comics Journal has a well respected source for a long time).

Those familiar with how a comics story is produced under the Marvel method, may have difficulty imagining how the pencil drawing for an entire story could be complete and still be in need of a plot to be added afterward by the writer, and Evanier and Morrow argued that Kirby’s creative contributions went well beyond the instructions he received from Lee. McMahon, however, acceded to Marvel’s motion to strike Evanier and Morrow’s testimony. She seemed skeptical of their status as comics “experts,” always placing the word in quotes, and expressed the view that they would not be able to add anything to the proceedings that lay persons, or non-comics-experts, couldn’t determine on their own. Also mitigating against the relevance of Evanier’s and Morrow’s testimony was the fact that they didn’t have firsthand knowledge of industry practices before 1963.

One of the experts who has often supported this version is Stanley Lieber, a.k.a. Stan Lee.

On Steve Ditko:

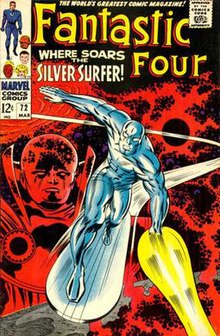

"I'd dream up odd fantasy tales with an O. Henry type twist ending. All I had to do was give Steve a one-line description of the plot and he'd be off and running. He'd take those skeleton outlines I had given him and turn them into classic little works of art that ended up being far cooler than I had any right to expect."And on the creation of the Silver Surfer:

"There, in the middle of the story we had so carefully worked out, was a nut on some sort of flying surfboard". He later expanded on this, recalling, "I thought, 'Jack, this time you've gone too far'"

Like I said. I doubt the Kirbys will win this. I'm not even sure they should. Jack Kirby made a massive contribution to the medium, but he was not a good businessman and he made some bad deals. Disney/Marvel have mistreated creators for decades but as long as they did it within the law, I'm not sure if the courts should get involved.

What I am fairly sure of is that we've seen absurd and destructive regulatory capture in the area of copyrights. The current system is unfair to actual creators. It erects barriers to entry and encourages media consolidation. It even allowed companies to snatch films out of the public domain. I hope the Kirbys win their case but the real fix for this problem needs to come from Congress, not the courts.